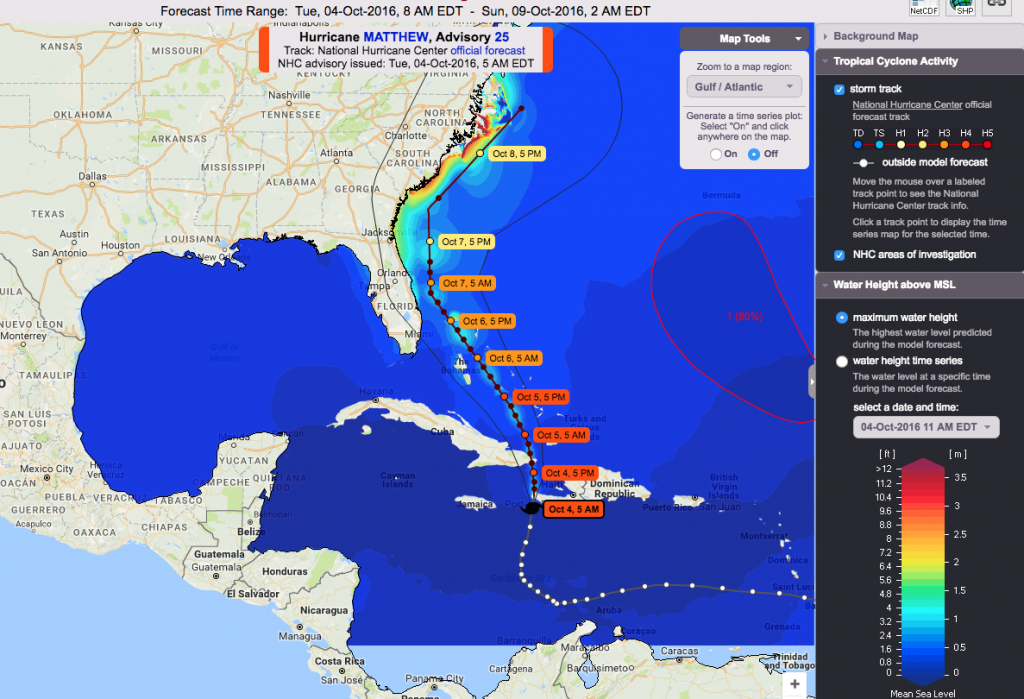

Models this week show storm surge from Hurricane Matthew could be as high as 12 feet in some coastal areas.

CHAPEL HILL, NC – As Hurricane Matthew slowly makes it way toward the U.S., RENCI’s Dell PowerEdge supercomputer, named Hatteras for the home of North Carolina’s most famous Outer Banks lighthouse, is working overtime to model the storm surge that Matthew could bring to communities along the Eastern Seaboard.

Hatteras, a 150-node M420 Dell cluster, runs the ADCIRC storm surge model every six hours when a hurricane is active. Visualizations of the models appear on the Coastal Emergency Risks Assessment website. The outputs from these runs are incorporated into guidance information by the National Weather Service, the National Hurricane Center, and agencies such as the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, FEMA, and local and regional emergency management divisions. The models are a tool used to help make decisions about evacuations, and where to position supplies and response personnel.

The work to apply high performance computing and data analysis to understanding dangerous storm surge is part of a long-term collaboration involving RENCI, the Coastal Resilience Center at UNC-Chapel Hill, and UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences. Over the last 10 years, Brian Blanton, a coastal oceanographer and director of RENCI environmental initiatives, has worked closely with Rick Luettich, director of IMS and principal investigator for the Coastal Resilience Center and IMS, and others to enhance and improve the ADCIRC coastal circulation and storm surge model.

ADCIRC was developed by Luettich and researchers at the University of Notre Dame. The researchers and developers who maintain the software and develop the visual models represent universities on the East and Gulf coasts as well as agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency, the National Weather Service, the National Science Foundation, and the Department of Homeland Security.

Every time the Dell system at RENCI computes another storm surge model for use by the emergency response community, Blanton is busy running a series of at least nine possible storm surge scenarios on the same HPC system. The process is much like ensemble weather forecasting, where meteorologists run a large number of weather models using slightly different initial conditions in order to account for the uncertainty in such a dynamic system.

The model output available on the web for Matthew can resolve the detail of coastal storm surge to a level of less than 200 meters, and the team’s current research could mean that storm surge models next year will provide even more detail and accuracy. “We are working on doing storm surge predictions the same way that meteorologists develop predictions for rain and wind speeds,” said Blanton. “It will provide high-resolution storm surge probabilities that account for uncertainty in the track and intensity of hurricane forecasts.” Blanton said the research team plans to acquire enough test simulations this year to be able to produce ensemble models regularly for hurricane season 2017.

In the meantime, Matthew could leave many North Carolinians and people up and down the East Coast in high water. To follow the storm’s progress and its potential storm surge, visit the Coastal Emergency Risks Assessment website.

Related links:

ADCIRC website

Coastal Resilience Center Website

Institute of Marine Sciences Website