No store-bought tomatoes can compare with sweet, juicy, still-warm-from-the-sun heirloom varieties found at midsummer farmers’ markets.

Foodie pleasures aside, can consuming locally grown fruits and vegetables and locally raised meat lead to better health and help to combat obesity? Does buying food grown neaby help the local economy by keeping family farms viable as North Carolina transitions away tobacco farming? Does ‘buy local’ equate with ‘go green’ because fewer fossil fuels and pesticides are needed to move food from the fields to the dinner table?

Alice Ammerman and her multi-institutional, multi-disciplinary research team investigate these and other questions through a project funded by the Gillings Innovation Labs at UNC Chapel Hill. Ammerman, a professor of nutrition in the Gillings School of Global Public Health and director of the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention at UNC, wants to understand the public health, economic, and environmental impacts of moving toward a local, sustainable food system. Her team involves experts in nutrition, public policy, economics and agriculture at UNC, Duke, NC State and NC A&T as well as software experts at RENCI who developed a tool dubbed the market locator.

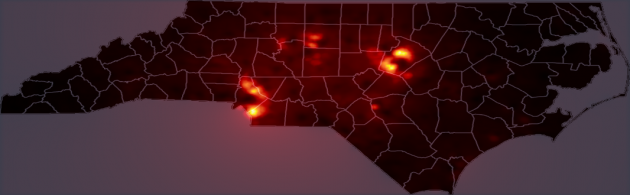

The RENCI market locator will use demographic data such as income, population density and the presence of other markets and grocery stores in the area, as well as data on travel times around the area, to pinpoint the best strategic locations for new farmers’ markets.

The current version of the tool calculates a score indicating the income potential for a market located within a specific census block. The tool calculates potential for every census block in North Carolina, which allows the user to compare clocks to determine where markets are likely to succeed to pinpoint existing markets that are under performing.

To determine score, the tool looks at drive-time circles of different radii around the market location, the net income within the drive-time circles and uses a site location model that accounts for competition from other farmers’ markets.

Ammerman’s team and RENCI software developers plan to improve the tool by studying data from farmers’ markets in Washington state to better understand who shops at farmers’ markets (Baby Boomers vs. Gen Xers, for example). By more accurately identifying which area residents are likely to shop at a market, the tool will be better able to choose successful market locations, said Charles Schmitt, director of RENCI’s informatics division.

Above: RENCI’s market locator shows strategic sites for farmers’ markets based on population density and demographics. Researchers are fine-tuning the tool looking at what groups are most likely to shop at the markets.

“You want to know how many people live within driving distance of a given location, but more importantly, you want to know how many of them are likely to shop at a farmers’ market,” said Schmitt. “There could be many factors that come into play, from income to age to education level.”

Putting markets where they are most likely to succeed will give other researchers the chance to study whether markets help the pocketbooks of local farmers, the health of market customers and the environment through its focus on locally grown foods.

For more information see:

Linking local sustainable farming and health

Improving health and economies