CHAPEL HILL, NC–Melanoma—the most serious form of skin cancer—varies in size, shape and severity, and although pathologists and researchers often intuitively differentiate between types of melanomas, the variations have never been formally quantified and documented.

A project involving RENCI and researchers in the UNC School of Medicine and the departments of computer science and statistics and operations research aims to change that by using image analysis techniques to improve melanoma classification. The research team, led by Nancy E. Thomas, a professor and M.D. in the School of Medicine’s dermatology department, examines images made from biopsy slides of both cancerous and healthy skin cells.

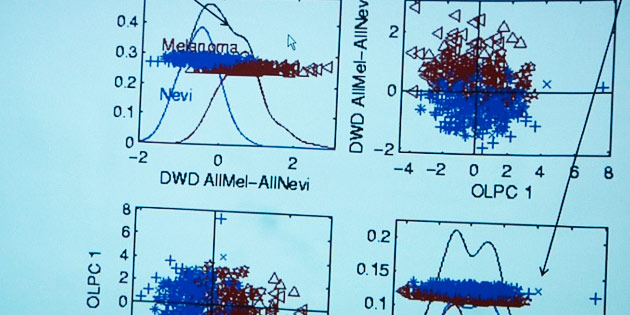

A team that includes RENCI Senior Visualization Researcher David Borland, Marc Niethammer, assistant professor in the UNC computer science department, and Steve Marron, a professor in UNC’s statistics and operations research department, uses the image data to train “smart” algorithms to identify physical characteristics of cells in the images, such as whether they are cancerous or benign, and the size, shape and color of healthy tissue and tumors.

The information that is extracted from the data can then be used to classify melanoma variations. These details also help the researchers develop evidence-based models of melanoma cell descriptions that in time could help doctors determine the seriousness of melanoma cases more quickly and with better accuracy.

The project uses specimens from numerous studies at UNC and other research hospitals, which are scanned in very high resolution. So far, the team has worked with data from about 300 specimens. RENCI’s Social Computing Room at UNC, with its floor-to-ceiling display across all four walls, makes the perfect environment for examining the scanned slides as well as the models that are created using the algorithm that learns to recognize image characteristics.

“The algorithm can be trained to do a variety of things,” said Thomas. “It can be trained to detect malignant versus benign, it can be trained to detect a melanoma with one mutation versus another, or it can be trained to pick out slides of patients with worse chances of survival or better. You can use a variety of different end points and see how well it predicts those end points.

“In the long term. We think this work might serve as a pathologist assist device, where it helps the pathologist quantitate certain features they are interested in and pull out new features,” she said.

The project received its initial funding from the University Cancer Research Fund, a revenue source created by the North Carolina General Assembly to accelerate the battle against cancer at the UNC School of Medicine and its Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.