It takes no more than watching the news to realize that homes and businesses along the U.S. East Coast face dangers from erosion, floods, and monster storms. Although North Carolina escaped most of the havoc caused by Hurricane Sandy, its Outer Banks constitute a vulnerable strip of land. The region’s fragile natural environments and popular tourist attractions are battered every year by tropical storms, nor’easters, and winds that erode beaches, shift sand dunes, degrade dune ridges, wash out roads, and sometimes threaten peoples’ lives and homes.

A North Carolina State University research team works to understand the dynamics of Outer Banks terrain using data on land elevation, sea levels, and coastal development and innovative visualization techniques developed through a collaboration with RENCI.

“We are providing quantitative research to support understanding of what is happening with this coastal terrain over time,” said Helena Mitasova, PhD, an associate professor in the NC State Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences (MEAS). “Visualization helps us get more get more insight from the data. It makes it easier to communicate our results.”

Mitasova and Laura Tateosian, PhD, a research assistant professor with the Center for Earth Observation at NCSU, began working with RENCI senior research data visualization software developer Sidharth Thakur, PhD, about two years ago through the RENCI at NC State Faculty Engagement Program in Applied Scientific and Information Visualization. The project involved analyzing a variety of data sources on coastal North Carolina, including digital elevation models (DEMs) derived from high-resolution LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) remote sensing surveys, aerial photography from the National Agricultural Imagery Program, U.S. Geological Survey data that uses transect lines running perpendicular to the coast to divide the region into segments, and data about the human impact on the Outer Banks derived from Chamber of Commerce occupancy receipts and National Park Service visitor counts.

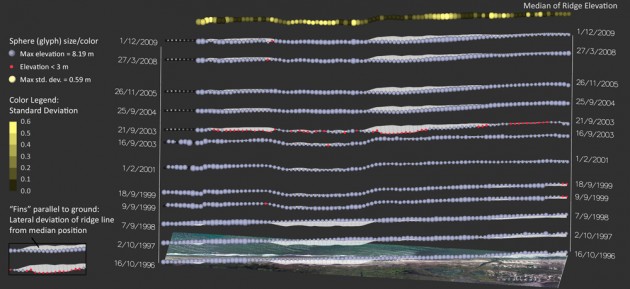

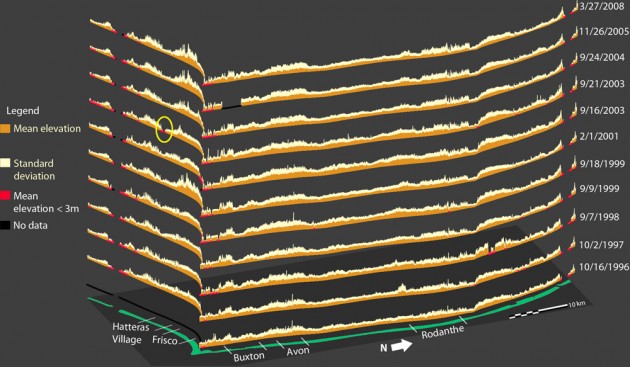

The researchers wanted to examine changes to the terrain over time, and to compare those changes with significant events such as Hurricanes Isabel (2003) and Irene (2011). Because they needed to combine different kinds of data and wanted to include time as a variable, standard visualization techniques were inadequate. The team developed holistic visualizations that used glyphs—small visual objects such as dots or cones—and color over a series of time steps and interactive, exploratory visualizations to show phenomena such as changes in dune ridgeline elevation before and after Hurricane Isabel, instances of dune overwash in the Rodanthe area from 1999 to 2011, and changes in the region’s popularity with tourists and how that relates to terrain changes and weather events.

Capturing both space and time

“The Outer Banks is a long, narrow geographical area and with Sid’s help, we’ve been able to represent that large spatial area, as well as time, in one image,” said Tateosian. “That’s a much more effective way to look at our data than to compare a whole series of single images.”

She said that visualizing the same geographical area over time steps that cover years allows the researchers to spot trends and to better understand the causes of coastal erosion. For example, by looking at ridgeline elevations before, during and after Hurricane Isabel, they can determine if elevations were already declining before the hurricane, how the storm affected the ongoing changes, and whether to expect continuing ridgeline declines after the storm.

It’s the kind of information that could help scientists understand the effects of coastal storms, waves and winds in a vulnerable area facing rising sea levels. The knowledge gained from the work could also help city planners and developers as they decide where to locate resorts or subdivisions, or aid emergency managers in determining whether to order a coastal evacuation.

“Sid was an enormous help in bringing fresh ideas to visualizing coastal terrain changes,” said Tateosian. “Traditional techniques represent distinct aspects of the data in individual images and make pairwise comparisons. That’s fine if you simply want to see if a dune is smaller this year than it was last year, for example. But what if you want to look at the long-term trend over five years or 10 years? It would become very difficult to compare the terrain features of a particular area over time—let alone a large stretch of beach over time. “This systems accounts for both the spatial element and the changes to terrain that occur over time.”

Mitasova hopes the visualization collaboration, funded in part by the Army Research Office and RENCI, will seed additional funding to study the dynamics of Outer Banks terrain. Her research plans include analyzing known vulnerable regions for patterns and adding new metrics to the analysis. Similar visualization techniques could be used to study the dynamics of other vulnerable terrains, such as mountainous regions that are prone to landslides, she said.

The research team looks forward to using a new visualization lab being built in the College of Natural Resources Center for Earth Observation, which will make their visualizations more accessible to other researchers and give more scientists the opportunity to learn about the techniques used in the RENCI collaboration. The researchers also plan to take their data into the NC State Social Computing Room, a RENCI facility planned for the D. H. Hill Library that will feature a floor-to-ceiling desktop on all four walls and will facilitate collaboration around large complex data sets.

“Working with RENCI really helped us get this project moving forward quickly and helped us think about our data in new ways,” said Mitasova. “There’s more to do, and we hope we can continue collaborating.”

Photo credit hburrussiii