Author: Brandy Farlow

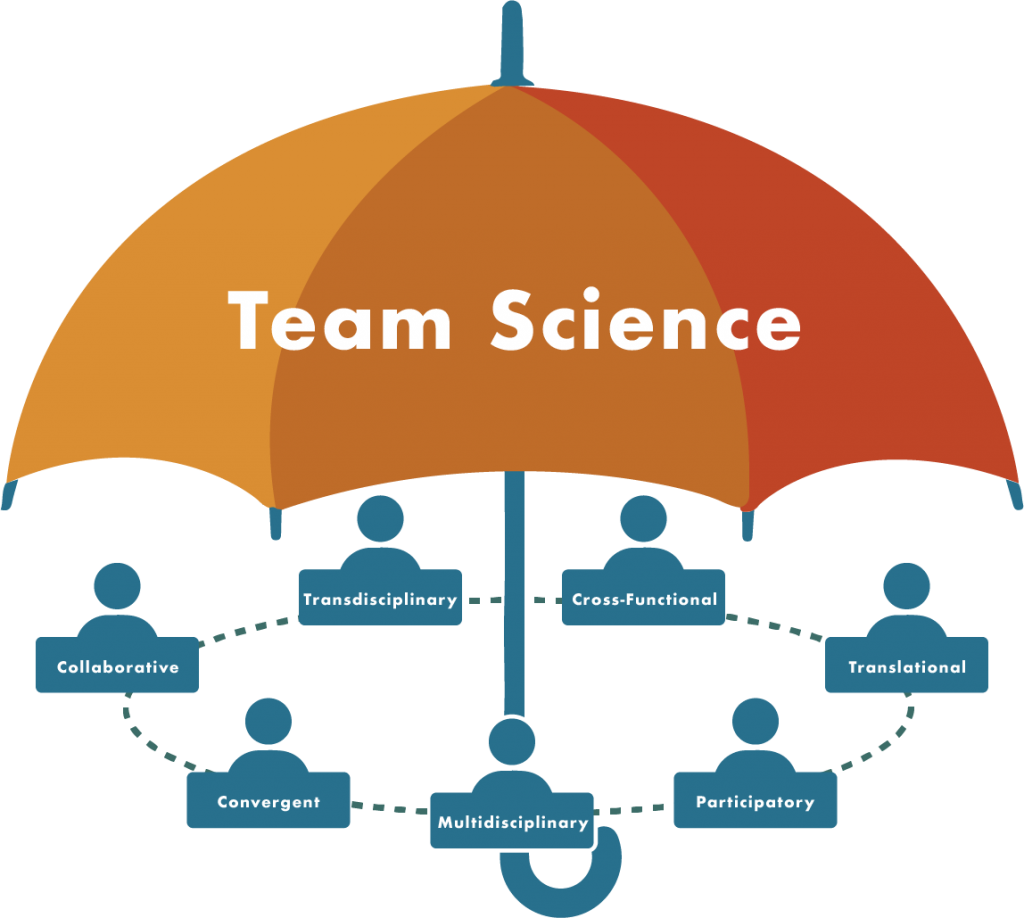

The term “big science” first made its way into academic literature in 1961 (article here). At the time, this was a means to discuss cooperative science pursuits (regardless of size) to tackle large, real-world problems. Since then, the term big science has come to have a different definition, but cooperative science efforts have been called multiple things, including transdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, collaborative, convergent, cross-functional, and, more recently, team science. Regardless of the naming conventions used, collaborative team science can be seen as any collaboration where multiple scientists work toward a common or interrelated research goal(s). While recognizing the critical role scientific collaboration will play in solving some of the so-called “wicked problems” humanity currently faces, collaborative science teams around the globe are struggling to recognize the importance of bringing these terms of collaboration under the same umbrella, recognizing the value of the scientific study of science teams, and promoting a clear path forward as a greater collaborative science community.

Of note, the International Network for the Science of Team Science (INSciTS), has been hosting annual conferences since 2010 and working to further research into the science of team science as a legitimate field of inquiry. That said, while INSciTS has done much to further our understanding of scientific teams, more work still needs to be done. Collaborative scientists need to improve their collective understanding of the science of team science and apply the field’s lessons to enhance funding options (for example, though NSF and NIH have been funding scientific collaborations for years–using different terminology–specific funding for the science of team science lags behind). By noting all collaborative science research pursuits as collaborative team science, the field will also benefit from increased researcher promotability for collaborative science tasks, better training opportunities, and a fostered recognition of the science of team science as a unique field of inquiry. This problem all begins with branding, because what we call it really DOES matter.

It is understandable and encouraged to have this varied collection of terms, defining the differences between collaborative team science pursuits, but we also need to emphasize what connects us. A researcher may, for example, be a translational scientist. These contributions should certainly be called out in the translational research space, but specifically understanding and noting a connection to “collaborative team science” or tagging this as a keyword in their publications, will allow the lessons they’ve learned about collaboration to be identified and applied on, for example, a non-specified multidisciplinary science team or a convergent team. This is branding, and it helps the structures, ideas, and best practices we learn in our individual branches spread to others who may benefit from what we have learned.

The importance of branding is recognized across industry, government, and academia. For a company or university, this may include colors, fonts, logos, tag lines, and beyond. For research fields, it is a bit different. Instead of colors, we brand a shared sense of purpose through language, conceptual frameworks, and methodologies. To enhance funding opportunities, gain traction as a legitimate field of academic inquiry, and encourage researcher promotability within the broad field of collaborative science, we have to use the same terminology. This is our branding. And this “branding” under one umbrella indicates to the world beyond our collaborations that we have a unified sense of self, a conceptual agreement, and the ability to collectively move research forward. Interestingly, as a field that seeks to bridge gaps between disparate teams, we should certainly recognize that such common vocabulary is a large lesson and initial need brought before any cross-functional team. It is fundamental to operation. If we do not use the same language, we cannot move collaborative science, and the science of team science, forward as effectively.

The term collaborative team science is required, serving as the unifying banner for all collaborative science efforts, appropriately defining the field, and leaving space to research methodology useful to the unique challenges scientific teams face (the science of team science). You may work in translation team science (biomedical specific), convergent team science (collaborations with industry), citizen science (collaborations with the general public), or multidisciplinary science, etc., but we are all under the same larger umbrella. We need to acknowledge that umbrella and apply the term collaborative team science (alongside other identifiers, such as convergent or translational science) in our publications. This will promote searchability in our research, create a thematic and unifying term across these groups, and promote the study of collaborative team science for the benefit of all individuals involved in research collaborations.

Unfortunately, the world of science teams is currently fragmented, and the literal terms of collaboration are not mutually agreed upon. Team, convergent, collaborative, transdisciplinary, citizen, cross-functional, and translational science are all used extensively across the literature on team collaborations in the sciences. In some cases these are owned by scientific sectors (translational science, for example, is specific to biomedical science) or funding agencies (NIH writes about team science, while NSF seems to fund convergent science). While each of these terms promotes a similar concept (collaboration across varying science disciplines), the lack of recognition and use of a unifying term creates a tension that makes it hard for scientific teams to have a banner under which they can train, organize, become funded, incorporate leading practices, and pursue what is best for the team members, the team, and their research. Collaborative team science needs to be branded under one common term to move forward, and we all need to start using that term when we discuss our work with the world beyond our laboratories, organizations, and classrooms.

Interested in learning more about team science? Check out RENCI’s new Accelerating Collaborative Team Science (ACTS) webinar series. To view recordings from previous events, checkout our YouTube channel.